In 1842, The Hand-Book of Needlework by Miss Lambert explained that “no feminine art affords greater scope for the display of taste and ingenuity than that of needlework. The endless variety of form which it assumes…each in their turn serving as graceful occupations for the young, and an inexhaustible source of amusement for those in a more advanced period of life…”

Indeed, the Luzerne County Historical Society has several needlework samplers in its collection that were made by girls and young women during the early 1800s. Needlework was a skill that was taught, generally by mother to daughter or by female instructor to student. Often a girl would learn to stitch her first sampler under the eye of her mother, as early as age four or five. Stitching a sampler helped a girl to learn how to sew, while also reinforcing her knowledge of her letters, and demonstrating her family’s gentility. Having the skill and means to produce decorative needlework implied that the stitcher (and her family) had what historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has called “rural refinement.” A framed piece of needlework on the wall became an essential part of gentility, an aspiration for many during the early 1800s – it showed that not only could the family afford to pay for lessons for their daughter, but that they did not need her at home doing chores and housework.

LCHS is fortunate to have two samplers in the collection that were made by members of the Swetland family who built and lived in the Society’s Swetland Homestead for generations. Thanks to a recent grant from the PennEast Pipeline, we were able to clean the samplers and reframe them in acid-free materials to help preserve them for centuries to come.

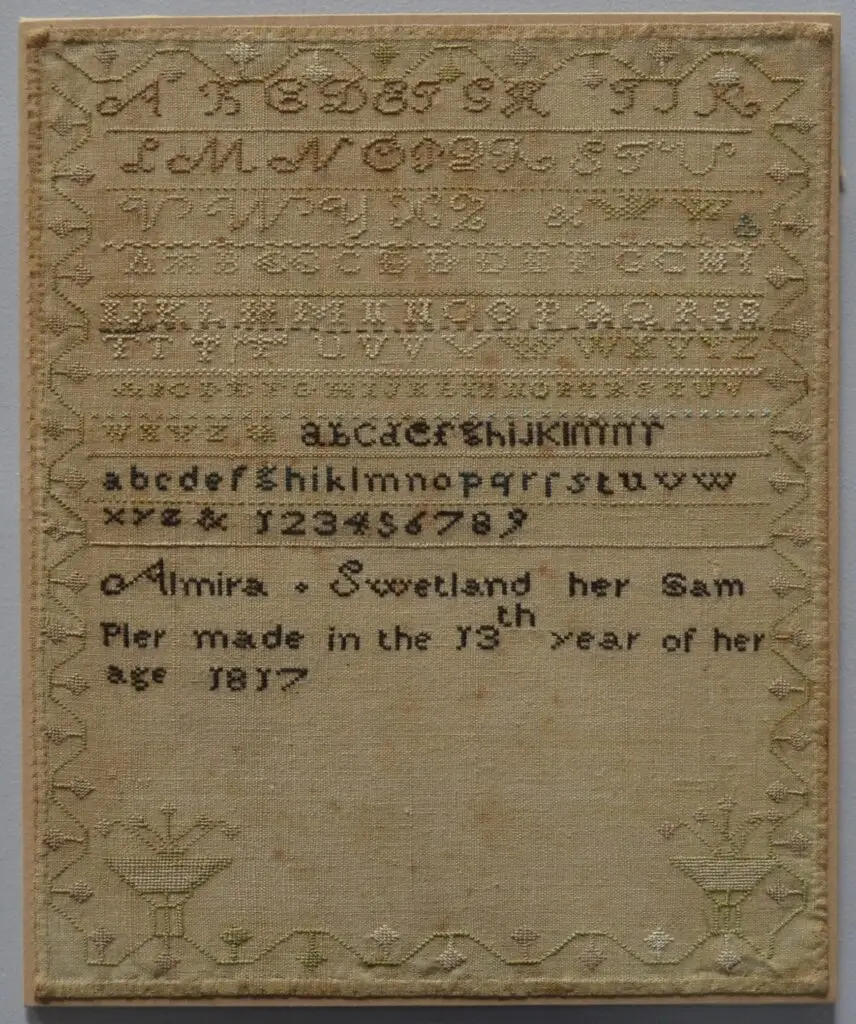

The older of the two samplers was made by Hannah Swetland, daughter of Joseph Swetland and granddaughter of Luke Swetland, who built the earliest part of the Swetland Homestead. Hannah was born in 1793 and made this sampler when she was 12 in 1805. It shows a simple style, in band form, with rows of letters and borders. It has characteristics of a marking sampler, which helped a girl learn to cross-stitch initials so she could mark her family’s household linens. That way, if the items were sent out for laundering, they could be identified and returned to the right place.

Hannah married James Hughes (1780-1870) in 1813 when she was 20. James was from Berks County and reportedly came here to build a mill for Hannah’s father. The couple had ten children, eight of whom lived to adulthood. Sadly, one of their children, Sarah, died at the age of five while playing “crack the whip.” She was on the end and when they cracked the whip, she fell into the fire and was badly burned, causing her death. Their son Hugh, died at age 25 when he was burned to death in an explosion of a camphine lamp in a canal boat in Philadelphia. But seven of their children lived fairly long lives. Most of the family is buried in the Forty Fort cemetery. In his will, James referred to Hannah as his “beloved wife,” and the couple had a long marriage. Hannah died in 1872, aged 79. Her sampler was passed down in the family.

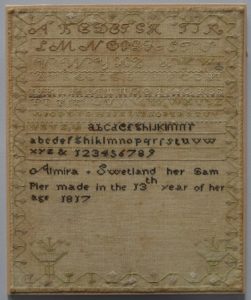

The second sampler was made by Almira Swetland, daughter of Belding Swetland, who was Joseph’s brother. Almira was also a granddaughter of Luke Swetland. She and Hannah were cousins. Almira was born in 1805 and made this sampler in 1817 when she was 13. The sampler is unfinished, but was intended to have a decorative scene at the bottom. Both samplers show some fading and were probably much brighter when first made. A pink and green color scheme for floral borders and letters was popular on samplers from this period. Both of these samplers were stitched on linen fabric with silk thread, materials that would have been available from local shops.

Almira Swetland married William Merrifield, who was from New York state. They had seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood, including Edward Merrifield who was a well-known Scranton lawyer and wrote Luke Swetland’s Captivity (which is available for purchase in our online shop here). Almira died in 1880, aged 75. The sampler was passed down through her family and was given to the Historical Society in 1961, just a few years after the Swetland Homestead was given to the Society in 1958. The newspaper covered the gift of the sampler and some other items, by Cornelia MacDermott of Kingston, who was Almira’s great-great-great granddaughter.

Like Almira’s sampler, many samplers were handed down from generation to generation along female lines. We generally think that women could not own property during the 1700s and 1800s. And, for most women this was true legally. But, in reality, there is abundant evidence to suggest that women (and their husbands and fathers) understood household textiles, as well as personal items brought to the marriage by the wife, to belong to her. Items like samplers were often passed down from mother to daughter or from aunt to niece.

Samplers started to go out of style as the curriculum and prevalence of town schools changed. Girls were able to attend public schools and focused on reading, writing and arithmetic, rather than on sewing, painting and dancing. By the late 1800s, crazy quilts and needlepoint took the place of samplers as older women pursued their creation as a leisure activity. But, the samplers that remain with us today demonstrate that they were more than just a simple way to learn one’s letters – they became cherished artifacts intrinsically related to the ancestor who made them.