Certain parts of our culture are as old as time itself. Other things remain unchanged throughout the course of their lifetimes, creating a rich, deep tradition. Motorsports is one such activity. Although only dating back about 150 years or so, it has remained almost exactly the same throughout that time. The first car to cover a set distance, wins. Simple, cut and dried, efficient. Sure, the cars, locations and distances might change, but the goal never does. An old adage says that auto racing was invented the moment the second car was completed. While this is an exaggeration, it’s not much of one. The first motor cars began tooling around Germany in 1886. Less than twenty years later, major motor racing, in a form that would be recognizable to us even today, was born. In 1903, the British began the Gordon Bennett Cup, the first major international automobile race. By 1906, the French had organized the first “Grand Prix,” setting up the foundation for the open-wheel racing world that exists today, with modern-day Formula 1 at its peak. However, the Europeans were not the only ones catching the need for speed.

Certain parts of our culture are as old as time itself. Other things remain unchanged throughout the course of their lifetimes, creating a rich, deep tradition. Motorsports is one such activity. Although only dating back about 150 years or so, it has remained almost exactly the same throughout that time. The first car to cover a set distance, wins. Simple, cut and dried, efficient. Sure, the cars, locations and distances might change, but the goal never does. An old adage says that auto racing was invented the moment the second car was completed. While this is an exaggeration, it’s not much of one. The first motor cars began tooling around Germany in 1886. Less than twenty years later, major motor racing, in a form that would be recognizable to us even today, was born. In 1903, the British began the Gordon Bennett Cup, the first major international automobile race. By 1906, the French had organized the first “Grand Prix,” setting up the foundation for the open-wheel racing world that exists today, with modern-day Formula 1 at its peak. However, the Europeans were not the only ones catching the need for speed.

In 1904, William Kissam Vanderbilt II commissioned the Vanderbilt Cup (to learn more, visit http://www.grandprixhistory.org/vand.htm) and launched the United States into the international racing scene. Many smaller contests began sprouting up all across the US and Continental Europe. The Wilkes-Barre Automobilists Club (which had been founded in 1905 to promote auto safety), noting the large crowds drawn to Long Island, New York, for the Vanderbilt Cup, decided to organize a motor race for Memorial Day 1906. But what type?

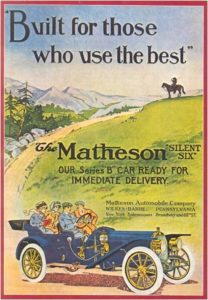

The first “Giant’s Despair Hillclimb” could have been held anywhere. The Wyoming Valley is naturally surrounded by hills and mountains, ranging from barely noticeable to fierce, sheer drops. The race itself could have been a road race, on mostly flat terrain. But once it was decided that what eventually became “the Giant” would be a hillclimb, it seemed only natural that Wilkes-Barre Mountain would get the nod. Built as part of the Wilkes-Barre-Easton Turnpike back in the 1840s, the road over Wilkes-Barre Mountain was the final obstacle that freight and passengers had to face before reaching the city from Philadelphia, and was considered a challenge. The hill rises 690 feet and at times has a 20% incline. Many accounts tell of wagons on rainy or snowy days simply sliding down into Wilkes-Barre, making the final leg of the trip in record time, or in pieces. By the dawn of the 1900s, the hill was a known entity, so much so that the local Matheson Automobile Company used it as a proving ground for their then-$4500 Silent Six autos, before sending them to their Broadway showroom (see the photo at right).

The original “Wilkes-Barre Memorial Hillclimbing Contest” took place on Memorial Day 1906 under the sanction of the American Automobile Association (AAA) and was promoted by the Wilkes-Barre Automobile Club. Dozens of entries showed up and the classes were based on list price, with six classes for cars costing less than $1000, $1500, $2500, $3600, $5000, and $9000, respectively, as well as a seventh, free-for-all class for stripped-down racing cars. The next day, the Wilkes-Barre Record posted a recap that would go down in history: “Up the most severe hill climbing course on which an automobile race was ever run in this country, a number of fine cars struggled yesterday morning in the presence of thousands of people, and the honors went to an English Daimler 45 horse power car run by H. N. Harding, which made the best time of the course in the two events in which it was entered. The course was up Wilkes-Barre mountain christened by the automobilists “a Giant Despair,” where the grade in places is as high as 26%…” While the race would officially remain the “Wilkes-Barre Memorial Hillclimbing Contest” for a few more years, it would from then on be more familiarly known as “Giant’s Despair.”

The 1907 event was the largest motor race in American history at the time (in terms of entries, with more than 150) and was won by the local favorite – Matheson cars – built a mere ten minutes away in Forty Fort, PA, breaking the two-minute mark with a 1:59 time. In just year two, the race was already making waves on the international scene as Fiat sent its pre-war Grand Prix ace Ralph DePalma to tackle the hill. However, the Giant proved too much for DePalma – he slid off the gravel course before the race had even begun during an untimed practice run.

In 1908, local coal magnate, and racing enthusiast, John Welles Hollenback donated a sterling silver trophy, valued at $5000, to be engraved with the name of the winning driver each year. The Hollenback Trophy would last until 1962 when it was replaced with the Bud Faust Trophy (named after the popular competitor). Willie Haupt was the first to claim it in a Chadwick (see the photo at left), while in 1910 Ralph DePalma returned with a 200bhp Fiat and shattered the track record with a 1:28.4. This was after he caused quite a stir testing the Fiat by hammering back and forth down Market Street in nearby Kingston, PA, before the race! However, it is probably Louis Chevrolet’s 1909 entry that is most famous. While he didn’t win, Chevrolet rolled his Buick at the famous “Devil’s Elbow” corner, narrowly missing a crowd of spectators. He was unhurt, and witnesses say he lit a cigarette as he walked away from the wreck cursing in French.

In 1908, local coal magnate, and racing enthusiast, John Welles Hollenback donated a sterling silver trophy, valued at $5000, to be engraved with the name of the winning driver each year. The Hollenback Trophy would last until 1962 when it was replaced with the Bud Faust Trophy (named after the popular competitor). Willie Haupt was the first to claim it in a Chadwick (see the photo at left), while in 1910 Ralph DePalma returned with a 200bhp Fiat and shattered the track record with a 1:28.4. This was after he caused quite a stir testing the Fiat by hammering back and forth down Market Street in nearby Kingston, PA, before the race! However, it is probably Louis Chevrolet’s 1909 entry that is most famous. While he didn’t win, Chevrolet rolled his Buick at the famous “Devil’s Elbow” corner, narrowly missing a crowd of spectators. He was unhurt, and witnesses say he lit a cigarette as he walked away from the wreck cursing in French.

The race was an incredible hit as the speed and skill of the drivers attracted massive crowds to the mountain. The 1907 race saw 40,000 spectators while the 1908 and 1909 races drew over 50,000 each. The 1911 Wilkes-Barre Record Almanac estimated nearly 75,000 people saw DePalma’s record run in 1910 (for more on the 1910 race, visit https://www.firstsuperspeedway.com/sites/default/files/Giant’s_Despair_Hill_Climb_De_Palma.pdf). The 1916 Hillclimb was so big that a strike of street car employees of the Wilkes-Barre Railroad Company that had lasted for over a year, ended just before the 1916 event in order to accommodate the expected crowds.

Despite the attention and large crowds, the Hillclimb rarely, if ever, made money and was always in danger of going under. The 1909 climb alone lost $700, a staggering sum at the time. By 1910 there were serious rumblings within the Wilkes-Barre Automobile Club to drop the Hillclimb and focus on road improvements within Wilkes-Barre. The only reason that the 1910 climb occurred was that the Automobile Club sold medals to “boost” the event. Boosters paid $1 each for a medal, with all the funds going to the climb. However, it was a short-term gain, and in 1911 the Hillclimb was scrapped and not run again until 1916. Despite that year’s success, the outbreak of World War I, followed by the Great Depression, and then World War II, meant the Giant would lay fallow until 1951.

Stay tuned…Part 2 – “Reawakening the Giant, 1951-1972,” will be posted in a few weeks!