Lewis Hine. Noon hour in the Ewen Breaker, Pennsylvania Coal Co. Location: South Pittston, Pennsylvania, 1911.

Images of miners covered in black coal dust and Lewis Hine’s iconic photographs of breaker boys come to mind when many people think of the Anthracite coal region of Pennsylvania. These images evoke important memories and stories about the coal region of the Wyoming Valley. But how often do we think of the women in coal country, the wives of the miners and the mothers of the breaker boys?

As fathers, husbands, and sons went down into the coal mines in coal country, wives, mothers, and daughters preserved daily life outside the mines. Daughters and other young women flocked to the silk and lace factories dotted across the Wyoming Valley. Older women – wives and mothers – worked inside the home. Families needed to eat, money had to be managed, and coal dust had to be cleaned.

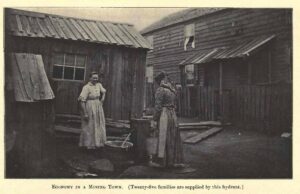

An average day for a miner’s wife began at 5 in the morning and ended when everyone was in bed. Women raised the children, cooked the meals, and cleaned the home. Coal dust made a wife’s work especially hard. Women heated the waters for her husband to bathe in when he returned from the coal mines, scrubbed the miners’ clothes, and cleaned the coal dust from the home.

Most families did not have running water inside their home, so women needed to get water from outside to bring it inside for bathing and washing.

Her family was not the only responsibility for many women in coal country. To supplement income, especially when her husband was out of work, women took boarders in. The majority of boarders were men who came to the coal region without family in search of work. Up to 20 or 30 men would board a three or four room house, often in shifts dependent on their schedule in the mines. Boarders paid the woman of the house to cook their meals, which was yet another way in which women engaged in business inside the home.

Opening her home to boarders was not the only way that women supplement a miner’s family income. Woman also raised chickens, grew vegetables, and washed laundry for other families. Others, yet, turned to the culm piles to look for discarded pieces of coal to sell for extra income as well.

Financial management was an important duty for wives also. As historian John Bodnar wrote, “[A miner’s] status and authority at home were usually secondary to their wives’.” When it came to money, women were most often in charge. Indeed, wives took authority over miners’ salary, stopping them at the front door to collect their paycheck. Her husband might have kept a small allowance for a drink in the bar after work, but the bulk of the money went directly to the hands of the wife.

Wives and mothers working inside the home may not be the image we think of when we think of the coal region, but women were an integral part of the family economy. These women did not often have positions outside the home, but that does not mean they did not work. In the coal industry, which did not always guarantee work to miners, the work done inside the home supplemented a family’s income. Outside the mines, a woman’s perseverance went in the coal patches.

Sources:

John Bodnar, Anthracite People: Families, Unions, and Work, 1900-1940. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1983.

Bonnie Stepenoff, Their Fathers’ Daughters: Silk Mill Workers in Northeastern Pennsylvania, 1880-1960. Susquehanna University Press, 1999.