The following is the first in a series of blog posts titled “FIC: Stories of Items “Found in Collection”. FIC is a museum industry term for items that were, well, found in a collection. The levels of provenance for these items often vary, and researching these items and tracking down why they are in your collection is a part of any curatorial employee’s job. This post focuses on a literal piece of Andersonville Prison, and the attempts of our Museum Manager, Allyson Earl, to figure out why we have it here in Northeast PA.

While going through our collection, I came across a curious object: a piece of wood, two inches long, from the stockade of the Andersonville Prison in Georgia (pictured left). Why would we, a local history museum in Pennsylvania, have a piece of a stockade from a prison in Georgia? Well, a brief note associated with the artifact says that it was given to George Lintern, a local, whose father was held at Andersonville.

Then who, exactly, was George Lintern’s father? After some digging, I was able to find records regarding one Joseph Lintern. He and his wife Amelia moved to the Wyoming valley in 1852. Joseph enlisted in 152nd Regiment Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery, Company A on October 30, 1862. Two years later, detachments of Company A and B of the 152nd regiment were stationed on union gunboats and participated in the Battle of Smithfield, Virginia. It was a small battle, but on February 1st, 1864, Lieutenant Thomas S. Harris and 37 of company A were taken prisoner, including Joseph Lintern.

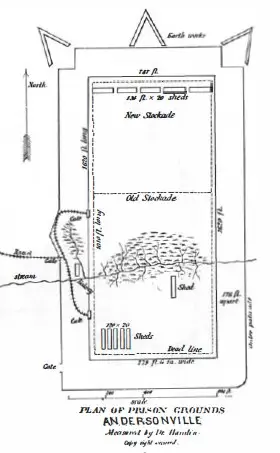

Lintern and other POWs were moved to the newly built Camp Sumter. Also known as Andersonville Prison, Camp Sumter is notorious for its high death count and awful living conditions. Lintern died just four months later in June of 1864. By then, the camp was overpopulated by 16000 prisoners, and had to be expanded, though it didn’t fix the problem. Overcrowding lead to strained resources and even structural problems. The main source of water for the prisoners was a stream that ran through the center of the camp. The banks eroded away only a few months in, forming a swamp which was the prefect breeding ground for disease-causing bacteria. (Pictured Right: Plan of Prison Grounds, 1865, courtesy of NPS/Andersonville National Historic Site)

Overcrowding and disease were not the only cause of death, however. Around the camp, about 19 feet from the stockade, was a simple fence known as the ‘deadline.’ Any prisoner who crossed the line, e ven just to reach the fresher water upstream, was shot without warning. In addition, prisoners were given very little rations or wood for fire, and were responsible for building their own shelters without many materials. By the time Camp Sumpter was closed in May of 1865, 13000 of its 45000 prisoners had died.

ven just to reach the fresher water upstream, was shot without warning. In addition, prisoners were given very little rations or wood for fire, and were responsible for building their own shelters without many materials. By the time Camp Sumpter was closed in May of 1865, 13000 of its 45000 prisoners had died.

The site changed hands a few times, from private ownership to the Georgia Department of the GAR to the Women’s Relief Corp, but was finally donated to the people of the United States in 1910. In 1970, the site was designated a national historic site. It is now administered by the National Park Service, and includes the Andersonville National Cemetary and the National Prisoner of War Museum. Check out their website (https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/index.htm) for more information and even an audio tour of the site.

If you want to learn more about Luzerne County’s participation in the Civil War, we have quite a few interesting resources at the research Library including History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, a collection of Civil War autographs collected by E L Dana when he was imprisoned in Charleston, South Carolina, and copies of Civil War letters by Levi Lewis to and from his family. In addition, we’re selling Gone But Not Forgotten by Ryan L. Lindbuchler in our gift shop and online, which lists some 9,000 veterans in 196 cemeteries and details 38 biographies of Civil War veterans from Northeastern Pennsylvania.

- Allyson Earl – Museum Manager