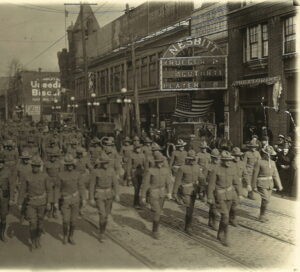

The 1918 strain of influenza was unique among most types of flu, as it had a high mortality rate among 15 to 34-year-olds, rather than the oldest and weakest of the population. By the time what we now incorrectly call the “Spanish Flu” was over, it had even lowered the life expectancy across the United States. It directly affected about one-third of the world’s population and caused about 25 million deaths. Unfortunately, despite all that, on Sept. 27, 1918, Wilkes-Barre like many other cities before them, held a Liberty Loan Parade to raise money for the American war effort in World War I. It was quite the spectacle. (Pictured below right)

Featuring a procession of floats, marching bands, city and state police on horseback, and many local groups including veterans, knights templar, committees of the parade, the fire department, and local service organizations. Many local businesses also took part including the Vulcan Iron Works, Titlow Knitting Mill, Fowler Dick and Walker, and Planter’s Peanuts, just to name a few and onlookers of the parade took up over 3 miles of the city. Such a large gathering of people exacerbated the spread of Influenza and the 1918 pandemic.

It is reported that the first cases of the flu came to Pennsylvania in mid-September. By October 1, 1918, when the Department of Health of the Commonwealth closed bars, theaters, public gatherings, and public funerals across the state, the Wyoming Valley already had a shortage of nurses, doctors, and space because of World War I. At a rate of 100 cases per day, even as emergency hospitals were opening across the county, Wilkes-Barre City Hospital could not take any more patients by as early as October 11.

Despite all this, however, masks were not made mandatory in Pennsylvania like they were in some other parts of the country, though locals wore them and local newspapers routinely shamed ‘Mask Slackers.’ Instead, a letter from the Commissioner of Public Health of Pennsylvania on October 22nd detailed instructions to treat patients through the pandemic. In addition to the use of full-body gowns and antiseptics, the commissioner recommended: “masks made by applying eight layers of surgical gauze, or two of butter cloth, to the convex surface of a wire tea strainer about four inches in diameter, which is molded to fit the face from above the tip of the nose to below the point of the chin and secured to the head by tapes, with the gauze changed every hour and boiled half an hour, sun-dried and used over again.”

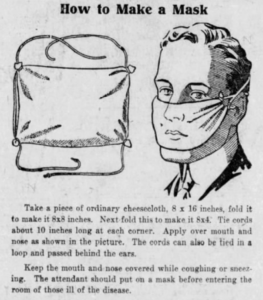

I was interested in how these measures compared to the ones we’re wearing in our current pandemic. Unfortunately, I could not find a 4” tea strainer to make my reproduction mask, but even in 1918 a wide variety of masks were used by both medical professionals and the public. Newspapers published various patterns for multiple styles of face masks. The Edmonton Journal published an illustrated guide designed for the average person to use. It calls for an 8 x 16” piece of cheesecloth, folded longways twice to make an 8 x 4” rectangle of four layers, and a cord tied at each corner to attach to the face. (Pictured below left)

Overall, it was quick and easy to make. I used cotton gauze and thin ribbon, both from Joann Fabrics. The problem is, gauze and the recommended cheesecloth are not really effective materials for use for a mask. Face masks work best if they filter vapor particles from the breath. You can see the open holes in the weave of the gauze, and, even though the four layers are better than just one, it has a minimal effect because of the very small nature of viruses (which are even smaller than bacteria). In addition, it doesn’t fit very well around the face. The illustration shows a man wearing the mask over his nose and mouth but not over his chin, and it does not seal around the sides. So whatever water vapor doesn’t make it through the gauze is funneled to the sides of the face without much filtration at all. The finished mask is pictured below.

So, I made a second, faux 1918 mask that could be used during the current pandemic. The CDC recommends multiple layers of cotton fabric for the best breathability and filtration. Cotton is positively charged and tends to attract the negatively charged coronavirus. In addition, the fibers that make up the fabric tend to be less sleek than synthetic fibers woven, and have more surface area. In addition, multiple layers of different kinds of fabric have been shown to be more effective.

To make the second reproduction mask, I put two layers of medium-weight cotton fabric (which I also got from Joann Fabrics) in between two layers of gauze and sewed them all together to hide the seams. I folded the mask at the sides to fit my face and sewed them down. I attached some pieces of twill tape to the sides as ties, and, the final touch: a stick-on aluminum strip to conform to my nose. It took maybe an hour to cut out and hand sew the entire thing. It won’t win any prizes for neatness, and shouldn’t be used for medical purposes, but it will pass for historical reenactment while still being effective.

There is a lot we don’t know about the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Partially because it is mostly overlooked amid the end of the world war and women’s suffrage, and partially because there is so much data to analyze and wade through before more information can be gleaned. Like Wilkes-Barre, Philadelphia held a Liberty Loan Parade on Sep 28th, which led to Philadelphia being one of the hardest-hit cities in the nation. The ‘Spit Spreads Death’ exhibit by the Mutter Museum organized information from death records to study what communities were hit in Philadelphia. Some of their exhibits is available online at http://muttermuseum.org/exhibitions/going-viral-behind-the-scenes-at-a-medical-museum/.

Sources:

Bufano, Matt. “Virus has renewed interest in 1918 pandemic.” Citizen’s Voice. Apr 11, 2020. Updated Jun 18, 2020. Accessed Jan 9, 2021. <https://www.citizensvoice.com/news/virus-has-renewed-interest-in-1918-pandemic/article_919ce87b-a7b6-5f40-b28b-84bc17b8e223.html>.

Science History Institute. Distillations (podcast). “Spit Spreads Death.” Apr. 14, 2020 <https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/podcast/spit-spreads-death-an-interview-with-jane-e-boyd>

Davis, Kenneth C. Smithsonian magazine. “World War I : 100 Years Later: Philadelphia Threw a WWI parade that Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu.” Sep. 21, 2018. <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/philadelphia-threw-wwi-parade-gave-thousands-onlookers-flu-180970372/>

Little, Becky. history.com. “When Mask-Wearing Rules in the 1918 Pandemic Faced Resistance.” May 6, 2020. <https://www.history.com/news/1918-spanish-flu-mask-wearing-resistance>.

Little, Becky. history.com. “First cases reported in deadly Spanish flu pandemic”. Apr. 30, 2020. <https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-cases-reported-in-deadly-influenza-epidemic>.

Little, Becky. History. “‘Mask Slackers’ and ‘Deadly’ Spit: the 1918 Flu Campaigns to Shame People Into Following New Rules.” Jul 17, 2020. <https://www.history.com/news/1918-pandemic-public-health-campaigns>.

Little, Becky. History. “Photos: Innovative Ways People Tried to Protect Themselves From the Flu.” Feb 4, 2020. <https://www.history.com/news/flu-masks-protection-photos>.

Influenze Encylclopedia: the American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919. “Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” <https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-pittsburgh.html#>.

Swestine. youtube.com. “I sewed and fit tested four different face masks…” Apr. 1, 2020. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZBbkn-g-vE>.

Hicks, Robert D. The Mutter Museum. “Why Spit Spreads Death?” Aug. 12, 2020. <http://muttermuseum.org/news/why-spit-spreads-death/>.

Ewing, Thomas E. Health Affairs. “Flu Masks Failed in 1918, But We Need Them Now.” May 12, 2020. <https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200508.769108/full/>.

Hauser, Christine. The New York Times. “Mask Slackers of 1918.” Aug. 3, 2020. <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/03/us/mask-protests-1918.html>.

Cohn, Samuel. The Conversation. “Face Masks: what the Spanish Flu Can teach Us About Making Them Compulsory.” May 1, 2020. <https://theconversation.com/face-masks-what-the-spanish-flu-can-teach-us-about-making-them-compulsory-137648>.

Lewis, Ed. timesleader.com. “Look Back: ‘Social Distance’ warnings in 1918.” Mar. 29, 2020. <https://www.timesleader.com/news/778163/look-back-social-distance-warnings-in-1918>.

Times Leader. timesleader.com. “‘Spanish Flu’ Was A Devastating Pandemic.” Aug 9, 2019. <https://www.timesleader.com/features/lifestyle/752046/spanish-flu-was-a-devastating-pandemic>.

Harvey, Oscar Jewell. “The spanish influenza pandemic of 1918: an account of its ravages in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, and efforts made to combat and subdue it.” Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. 1920. online. U.S. National Library of Medicine. <https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/bookviewer?PID=nlm:nlmuid-0266067-bk#page/10/mode/2up>.

Wilkes-barre Record. 20 Dec 1918, Fri. Page 31. “2,396 die in Pandemic: Influenza has hit luzerne county hard since october 1.” newspapers.com. <https://www.newspapers.com/clip/21941604/deaths-spanish-flu-1918-luzerne-county/>.

Wilkes-Barre Record. 28 Sep 1918, __. Page 9 & 18. “Paraders Fill Three Miles of City Streets.” newspapers.com. <https://www.newspapers.com/image/94272687/>.

Oakland Tribune, 24 Oct 1918, Thu, page 12. https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=63619054&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjgyMjU3OTQ5LCJpYXQiOjE2MDc3MjMwODMsImV4cCI6MTYwNzgwOTQ4M30.wSSC-eXhlHyPaA7c_Q7KbrKMRHqAaCfWelu2KnqZne4

Jordan, Douglas. “The Deadliest Flu: The Complete Story of the Discovery and Reconstruction of the 1918 Pandemic Virus.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Online. Dec 17, 2019. <https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/reconstruction-1918-virus.html>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “History of 1918 Flu Pandemic.” Online. Mar 21, 2018. <https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/1918-pandemic-history.htm>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Considerations for Wearing Masks.” CDC.gov. Dec 18, 2020. <https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprevent-getting-sick%2Fcloth-face-cover.html>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.

Encyclopedia Britanica. “Influenza pandemic of 1918-19.” Jul 07, 2020. <https://www.britannica.com/event/influenza-pandemic-of-1918-1919>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.

Godoy, Maria. “A User’s Guide to Masks: What’s Best at Protecting Others (And Yourself).” NPR.org. Jul 1, 2020. <https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/07/01/880621610/a-users-guide-to-masks-what-s-best-at-protecting-others-and-yourself>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.

Godoy, Maria. “Yes, Wearing Masks Helps. Here’s Why.” NPR.org. Jun 21, 2020. <https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/06/21/880832213/yes-wearing-masks-helps-heres-why>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.

Schive, Kim. “How do I choose a cloth face mask?” MIT Medical. Aug 6, 2020. <https://medical.mit.edu/covid-19-updates/2020/08/how-do-i-choose-cloth-face-mask>. Accessed Jan 12, 2020.