If you ever have driven in South Wilkes-Barre by either the Post Office or Fire Headquarters, you no doubt have noticed Gildersleeve Street. Gildersleeve Street is one of many Wilkes-Barre streets named after a person of note. However, unlike many of those other streets, Gildersleeve Street isn’t named after a politician or general. Instead, it is named for one of America’s most famous abolitionists, who also happened to reside in the city.

If you ever have driven in South Wilkes-Barre by either the Post Office or Fire Headquarters, you no doubt have noticed Gildersleeve Street. Gildersleeve Street is one of many Wilkes-Barre streets named after a person of note. However, unlike many of those other streets, Gildersleeve Street isn’t named after a politician or general. Instead, it is named for one of America’s most famous abolitionists, who also happened to reside in the city.

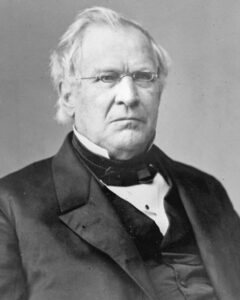

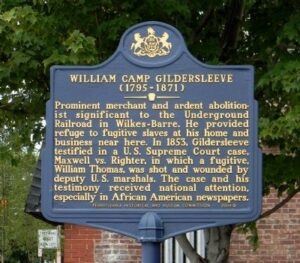

William Camp Gildersleeve (pictured left) was born in the rather fitting location of Liberty County, Georgia in 1795. His father Cyrus was a Presbyterian minister and plantation owner. Growing up in the Deep South, William was exposed to slavery firsthand and developed the hatred of “the peculiar institution” that was to drive him throughout his life. His father was hired as a pastor in our area in 1821 (first to a congregation in Kingston, then in Wilkes-Barre) and so William then arrived in the area where he would become nationally known. Aside from a brief two-year period where he and his family lived in Morristown, New Jersey, Gildersleeve spent his life bouncing around town living in a few different houses over the years on Union, and Franklin Streets, before eventually settling into a house on Main Street, between South and Ross Streets. It was here, fueled by his experiences as a teenager in Georgia, that Gildersleeve began his life’s work.

Now Wilkes-Barre, being settled along a major waterway, was a fairly busy stop on the Underground Railroad. And throughout the 1840s and 1850s, the city had two primary “stations”. The first, the Bethel A.M.E Church, then on State Street, and Gildersleeve’s Main Street home (below right). Gildersleeve’s “route” involved taking in runaway slaves from stops further South, and then, in the night, running them to Providence (now Scranton) and then onto Montrose as the next two stops on the way to New York State, and eventually Canada. Gildersleeve would also provide work for runaway slaves who decided to settle in Wilkes-Barre, either in his home (officially as paid domestic labor, but in actuality were midnight runners guiding other runaways north) or as employees at his Market Street dry goods store. Gildersleeve would also hide any runaway slaves who were being actively searched fo r, such as the case of a male slave who had to spend three continuous weeks underground in the Baltimore Mine, before his owner finally gave up searching for him and left the city.

r, such as the case of a male slave who had to spend three continuous weeks underground in the Baltimore Mine, before his owner finally gave up searching for him and left the city.

However, while Pennsylvania was primarily abolitionist, Gildersleeve was not universally popular. In 1837 he famously had his home ransacked and vandalized for allowing the Rev. John Cross to use it to speak on abolition, and two years later he was even tarred and feathered and paraded through the downtown after a mock trial at the county courthouse. No charges were ever filed against the attackers in either case, for Gildersleeve was seen by many as an instigator, and so finding a jury who would bring a conviction of his attackers was thought too difficult. Gildersleeve also never made any attempt to ever press charges, as he thought it just part of his mission. Gildersleeve also became a target of the group “The Friends of the Union” which was a conservative, pro-slavery sect of the Democratic Party that had quite a few prominent Wilkes-Barrians among its ranks.

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Gildersleeve was further motivated by the oppression he once again saw around him. Slave catchers being allowed to cross borders made even northern Pennsylvania seem like his home back in Georgia. Gildersleeve’s daughter, Mrs. Mary C. Sayre, once related a particularly troubling incident when a runaway slave was recaptured: “He was seized, thrown, someone put their feet into the fugitive’s mouth, and he was thrown onto the floor of a lumber wagon as if he were a dead hog. We were powerless to do anything under the Fugitive Slave Law.”

Gildersleeve became more and more emboldened and eventually was summoned to Federal Court in Philadelphia on charges of aiding runaway slaves. Appearing in person, Gildersleeve proudly plead guilty to the charge, only to have presiding Judge Robert Cooper Grier acquit him claiming they had “no proof against him”. Judge Grier was no fan of Gildersleeve’s however, as he proclaimed that William should be “hung up between heaven and earth.” And indeed, that he would be if Gildersleeve “was ever brought before me again”. Rhetoric like this stirred up tensions in the city, and with many other credible threats against him, Gildersleeve was escorted from the courthouse by a large group of Philadelphia area Quakers, who came without being asked to protect him.

While these incidents made William (in)famous in the County and in PA at large, it was an incident in 1853 that would propel him to national stardom. A runaway save named William Thomas had settled in Wilkes-Barre and was working at the Phoenix Hotel on River Street when he was discovered by two federal slave catchers. They set upon Thomas and attempted to shackle him. Thomas fought back however, with the fork and knife from one of the hotel’s tables he was setting. With torn clothes and the chains still affixed to one of his hands, Thomas fled across the street and made his way into the Susquehanna River. The slave catchers drew their firearms and began shooting at Thomas in the water (they would later claim in court that they had merely fired in the air, but Thomas had at least one graze wound on his body) Thomas cried out “You can shoot me, but you can never take me!”.

Hearing the shots, a large group made up of blacks and whites made their way onto the street and seeing what was unfolding, began to both interfere with the federal agents and shout encouragement to Thomas, including a few who chanted “Drown yourself Bill, drown yourself! Don’t let them take you!” As the crowd became more unruly, the agents withdrew, and Thomas was able to escape downriver where he was discovered, fairly badly injured, in a cornfield but a group of local women who nursed him back to health. He then was able to escape through the Underground Railroad to Canada with the help of William Gildersleeve. However, the incident had only just begun.

County Sheriff Gilbert Burrows, had not provided assistance to the slave catchers when called upon, but also then took the step of issuing a warrant for their arrest on grounds of inciting an insurrection on River Street and assault and battery with the intent to kill Mr. Thomas. Both Gildersleeve and Burrows were called to testify in the case, which after going through the federal circuit, found its way up to the US Supreme Court. This created the interesting situation of Gildersleeve once again being in front of Judge Grier, who had been promoted to the Supreme Court by President James K. Polk.

Despite being on the record as threatening to execute Gildersleeve if he ever saw him again, Judge Grier (pictured below left) refused to recuse himself from what was officially known as Maxwell v. Righter but was widely reported on in the newspapers as “The Wilkes-Barre Fugitive Slave Case”. Maxwell v. Righter was eagerly awaited by die-hards in both the North and South, as it was both a direct challenge to the Fugitive Slave Act, and a clash of states’ rights versus federal authority. The rivalry between Gildersleeve and Grier only added to the public’s interest.

Gildersleeve’s testimony became the highlight of the trial, with his line calling the Fugitive Slave Act an “unconstitutional……….foul disgrace to our country” being reprinted in papers across the country, and drawing both hate and vitriol from his opponents, as well as praise from national abolitionists including Fredrick Douglas, who in a speech went on to compare the Wilkes-Barre incident to the Boston Massacre when he said, “There, in immortal splendor, Wilkes-Barre will remain, until the Almighty has allowed us to work out the most glorious triumph of liberty in America”.

Gildersleeve then also went on the attack towards Grier himself, using the Judge’s own words against him when he said “While it may be humiliating to you, a tuppenny [sic] Pennsylvania Magistrate has a perfect right to arrest not only a deputy marshal, but a judge of the Supreme Court of the United States”. He also told Grier, as part of his testimony in front of the Supreme Court of the United States, that he was not at all intimidated by his open threat of hanging.

While it is no surprise that the Court ruled in favor of the slave catchers (a ruling reaffirmed in a later, second civil case taken before Judge John K. Kane stemming from Grier’s antics on the bench) Maxwell v. Righter not only put Wilkes-Barre on the map as an abolitionist haven right up with larger cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, or Cleveland, it made William Camp Gildersleeve a household name to both abolitionist and runaway slave alike. Fame he carried until his death in 1871, after having lived long enough to witness the abolition of slavery via the 13th Amendment.

Sources:

Brower, Edith (1923). Little Old Wilkes-Barre As I Knew It. WHGS Press

Kashatus, William C. (2007). “Finding Sanctuary at Montrose”. Pennsylvania Heritage.

Kashatus, William C. (2008). “In Immortal Splendor”. Pennsylvania Heritage.

Moss, Emerson I. (1992). African-Americans in the Wyoming Valley, 1778-1990. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Wyoming Historical and Geological Society and the Wilkes University Press.

Sayre, Mary (1911). A Bit of History of the Gildersleeve Family

Wedlock, Narria. (2016). “A Wilkes-Barre Abolitionist – William C. Gildersleeve” Ohio State Library.